Shannon Entropy

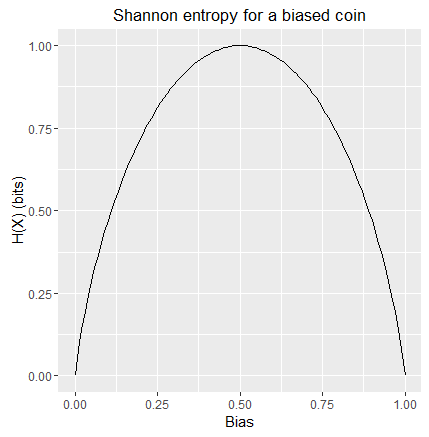

Shannon entropy is defined for a given discrete probability distribution; it measures how much information is required, on average, to identify random samples from that distribution.

Consider a coin with probability B (for bias) of flipping heads. We flip coins in a sequence (known as the Bernoulli process) and transmit each outcome to a receiver. We can represent the outcome of each flip with a binary 1 (heads) or 0 (tails), therefore on average it takes one bit of information to transmit one coin flip. Note that this method works regardless of the value of B, and therefore B does not need to be known to the sender or receiver.

If B is known and is exactly one half (i.e. a fair coin) then both outcomes are equally likely and it is still necessary to send one bit per coin flip. If B is exactly 0 or 1 then no bits need to be transmitted at all; i.e. the receiver can produce an infinite sequence of coin flips that exactly match the actual coin.

For values of B other than 0, 1 and 0.5 there exist schemes for communicating our sequence of coin flips with less than one bit on average per flip, most notably Arithmetic coding, which is near optimal; and the simpler but generally less efficient Huffman coding.

Huffman Coding Example

The probability of any given coin flip sequence S consisting of h head and t tail flips, and for a coin with bias B, is given by the following equation (from Estimating a Biased Coin):

$$ P(S|B) = B^h (1-B)^t \tag{1}$$

In our example B=`3/4`, and we will consider sequences of just two coin flips; hence there are just four possible sequences. The probability of each sequence is:

\begin{align} P(HH) &= 9/16 \\[1ex] P(HT) &= 3/16 \\[1ex] P(TH) &= 3/16 \\[1ex] P(TT) &= 1/16 \end{align}

Huffman coding assigns a code to each sequence such that more probable (frequent) sequences are assigned shorter codes, in an attempt to reduce the number of bits we need to send on average. Applying the standard Huffman coding scheme we obtain these code allocations:

\begin{align} HH &= 0 \\[1ex] HT &= 10 \\[1ex] TH &= 110 \\[1ex] TT &= 111 \\ \end{align}

We can now calculate how many bits we need to send, on average, per coin flip, by multiplying each sequence's code length with the probability of that sequence occurring, and summing over all four possible sequences:

\begin{align} AverageBitsPerSequence =&\, P(HH) \times 1 \text{ bit } + \\[1ex] &\, P(HT) \times 2 \text{ bits } + \\[1ex] &\, P(TH) \times 3 \text{ bits } + \\[1ex] &\, P(TT) \times 3 \text{ bits} \\[1ex] = &\, 1.6875 \text{ bits} \end{align}

Therefore this coding scheme requires 1.6875 bits on average to transmit the outcome of two coin flips, or 0.84375 bits per coin flip. Essentially, when `B \neq 1/2` we already have some information on what each outcome is likely to be, and therefore less than one bit of information is needed on average to inform the receiver of each flip.

Huffman coding captures some of the possible gains in efficiency but is not optimal in the general case, i.e. there exist more efficient coding schemes than the one described above. However, our example demonstrates a key aspect of the Shannon entropy equation; that multiplying each possible sequence's code length by its probability gives the code length we would need to send on average. This averaging over a coding scheme is precisely what the Shannon entropy equation describes:

$$ H(X) = -\sum_x{P(x)\log{P(x)}} \tag{Shannon entropy} $$

- `H()` is the convention/notation used to represent Shannon entropy; this is the value that is our average number of bits.

- `X` represents the set of all possible outcomes; in our example this is the four possible sequences.

- `x` represents an element of `X`.

We can clarify the equation further by applying the following logarithm law:

$$ -\log{x} = \log{\frac{1}{x}} $$Giving:

$$ H(X) = \sum_x{P(x)\log{\frac{1}{P(x)}}} \tag{Shannon entropy} $$Note that we have a sum over the product of each outcome's probability and a log term. The only difference between this and the above Huffman coding example is that the code length has been replaced with a log term; why?

Why Logarithms?

Logarithms are inherently a measure of information quantity. Consider transmitting long numbers, e.g. values between 0 and 999,999 (decimal). Each value can take one of out of a million possible states, and yet we can transmit each number with only 6 decimal digits. Noting that:

$$\log_{10}(1,000,000) = 6$$Note that the log base matches the number of symbols (0 to 9), and that the result is the number of (decimal) digits needed to encode a number with one million possible states. Hence we can obtain the number of bits needed to encode each number by changing the log base to two:

$$ \log_2(1,000,000) \approx 19.93 \text{ bits} $$In the general case we can say that `\log_b{N}` gives a measure of how much information (how many base `b` digits) we need to encode a variable with `N` possible states. E.g. for a coin with two possible outcomes we get:

$$ \log_2(2) = 1 \text{ bit} $$Why Reciprocals?

The Shannon entropy equation has this reciprocal within the log term:

$$ \frac{1}{P(x)} $$

By taking the reciprocal we obtain the number of possible states that could have that probability; we then take the log of that number of states to obtain how many bits, on average, it would take to distinguish between that many states. Multiplying by the probability of the state, and summing over all states, gives the Shannon entropy equation.

A Note on Number Bases

The Shannon entropy equation is agnostic with regard to logarithm base. Base 2 will give a measure of information stated in bits, which is a well understood metric and a natural choice when dealing with digital communications. However we can choose any base, e.g. base ten gives us a measure in decimal digits, base 3 in ternary digits, base 16 in hexadecimal digits, and so on. These different amounts obtained by using different log bases are all equivalent in terms of how much information they represent.

E.g. in the above example we stated:

\begin{align} \log_{10}(1,000,000) &= 6 \text { decimal digits } \\[2ex] \log_2(1,000,000) &\approx 19.93 \text{ bits (or binary digits) } \end{align}These two scalar measures of information describe an equal quantity of information, noting that:

\begin{align} 10^6 &= 1,000,000 \\[2ex] 2^{19.93} &\approx 1,000,000 \end{align}So in some sense we can say that information is the ability to identify a state within a set of possible states; and that to distinguish between more states requires more information. In fact Arithmetic coding encodes arbitrarily long messages as a single real number between 0 and 1, with arbitrarily long precision, i.e. a single variable with a great many possible states in which each possible value represents a different message.

In the general case Arithmetic coding results in a near optimal encoding of messages that is very close to the number obtained from the Shannon entropy equation. The Shannon entropy therefore should be considered as a low bound on the amount of information required to encode and send a message.

Huffman Coding Example (continued)

Recall that the above Huffman encoding example with `B=3/4` resulted in each coin flip being encoded with 0.84375 bits on average, but that Huffman tends not to result in an optimal encoding. We can now calculate the Shannon entropy for our example to find the number of bits per flip required by an optimal encoder:

\begin{align} H(X) = &\,P(HH) \cdot \log_2{\frac{1}{P(HH)}} \, + \\[2ex] &\,P(HT) \cdot \log_2{\frac{1}{P(HT)}} \, + \\[2ex] &\,P(TH) \cdot \log_2{\frac{1}{P(TH)}} \, + \\[2ex] &\,P(TT) \cdot \log_2{\frac{1}{P(TT)}} \\[6ex] = &\,\frac{9}{16} \cdot \log_2{1 \frac{7}{9}} \, + \\[2ex] &\,\frac{3}{16} \cdot \log_2{5 \frac{1}{3}} \, + \\[2ex] &\, \frac{3}{16} \cdot \log_2{5 \frac{1}{3}} \, + \\[2ex] &\,\frac{1}{16} \cdot \log_2{16} \\[4ex] = &\,0.466917186 + 0.452819531 + 0.452819531 + 0.25 \\[4ex] = &\, 1.622556248 \end{align}Recalling that we are encoding sequences of two coin flips, thus we divide by two to obtain a final Shannon entropy of 0.811278124 bits per coin flip. Slightly lower than the Huffman encoding figure of 0.84375 bits per coin flip, as expected; i.e. the Huffman coding is not optimal but is near optimal.

For completeness figure 1 shows the Shannon entropy for a biased coin:

Shannon entropy for a biased coin with bias B

Colin,

October 17th, 2016

Copyright 2016 Colin

Green.

Copyright 2016 Colin

Green.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License